061 #cities

A new year's post about the pace of change, on working with architects, and keeping a balanced outlook on progress.

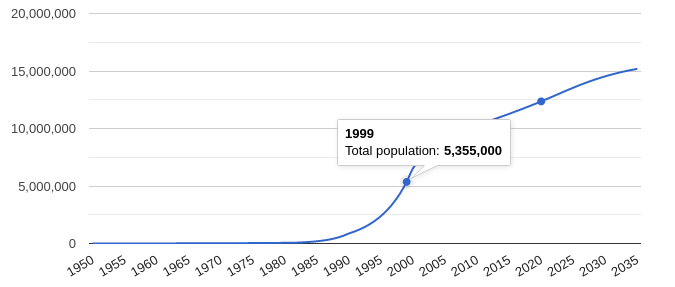

Between 1998 and 1999, Shenzhen added 1 million residents (chart via Population Stat) - in just 12 months, the city's population increased by almost a quarter! Equally hard to imagine, around the middle of the century, 1'700 miles (2'700 km) of the Alaska Highway were laid in just 234 days. Disneyland was famously built in a little over one year. And yet...the Van Ness bus corridor proposed by San Francisco in 2001 was recently delayed again to 2021. ...So what? Why not take the time to consider all options, evaluate every opinion? The facts above via post by Patrick Collison can help us to reflect on the velocity of human accomplishment: a variable that many rightfully question as determinant of progress.

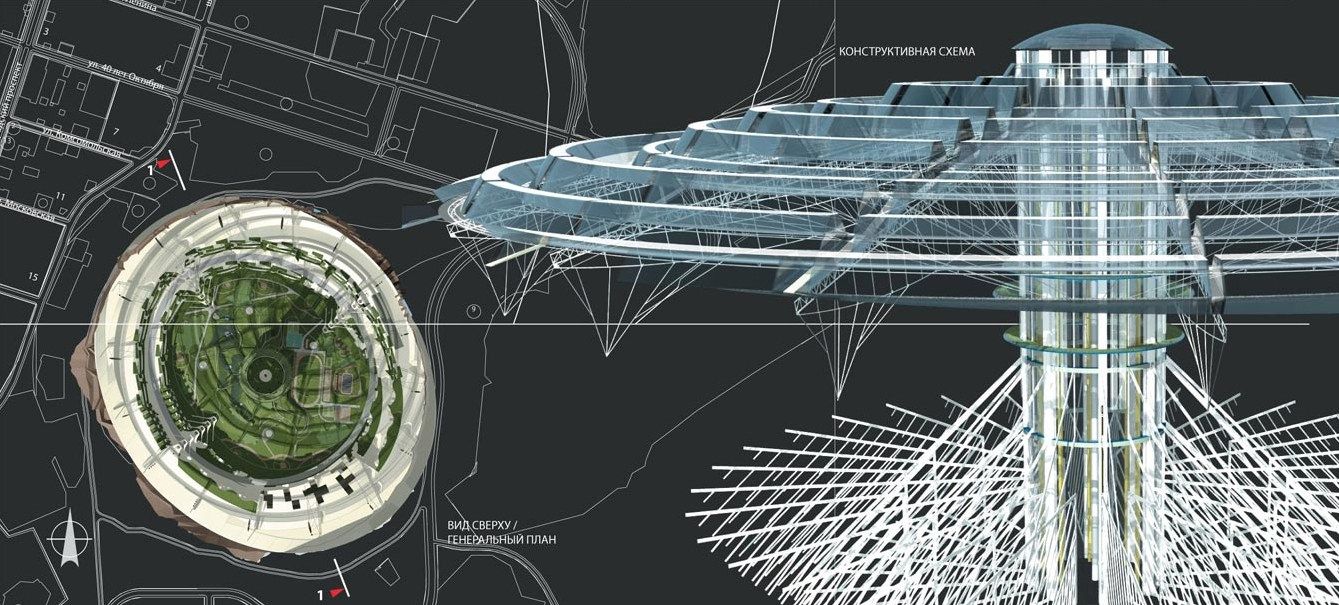

In 2010, architects from AB Elis announced an ambitious, science-fiction inspired project to create a domed city inside of a huge abandoned mine in Siberia, their speculative ideas urged by impending geological and ecological collapse in the surrounding territory. Construction was meant to get underway by 2020, though today I can find no signs of life. The concept and sketches of a great underground city and its heat-trapping dome doubtless inspire dreams - and plenty of indignation - in people. Daring to dream big is one of the things architects do when they make leaps of imagination from art to construction. Without the license to imagine, there is no innovation: stagnation looms. Without a pragmatic, relentless drive to realise your vision, the ability to win over the attention and resources of your fellows, the gutso to see a project through, our dreams die in the notebook, on the chalkboard, in the git repositories and pitch decks of modernity. And some big ideas can well take more than just a decade or two to settle in.

Welcome to the #future on #Zukunftstag. Wir bereiten uns auf #datawalks mit unserem Happy Lil' PrintrPi 🤖 vor. Habt ihr das verpasst? Mehr im 🔙Blogpost: https://t.co/OYeMaOVYbR #Kinder für #civicurbanism pic.twitter.com/rqaJ2doEIg

— cividi (@cividitech) November 14, 2019

It's awe inspiring to see people patiently build things one brick at a time, especially if we can relate to the fascinating and frustrating process of constructing a puzzle or a LEGO city. In that sense am grateful to have worked with great customers and amazing colleagues, experienced exotic settings for the application of my craft, seeing a number of interesting ideas come to life, patiently building on the practical benefits and use cases for open data one hack at a time. I was in a community of people who generally drove the results and lessons further, and tried to put my faith in people to whom I did not feel the need to prove myself. At one point, I jumped at the chance to do some work with some really good architects.

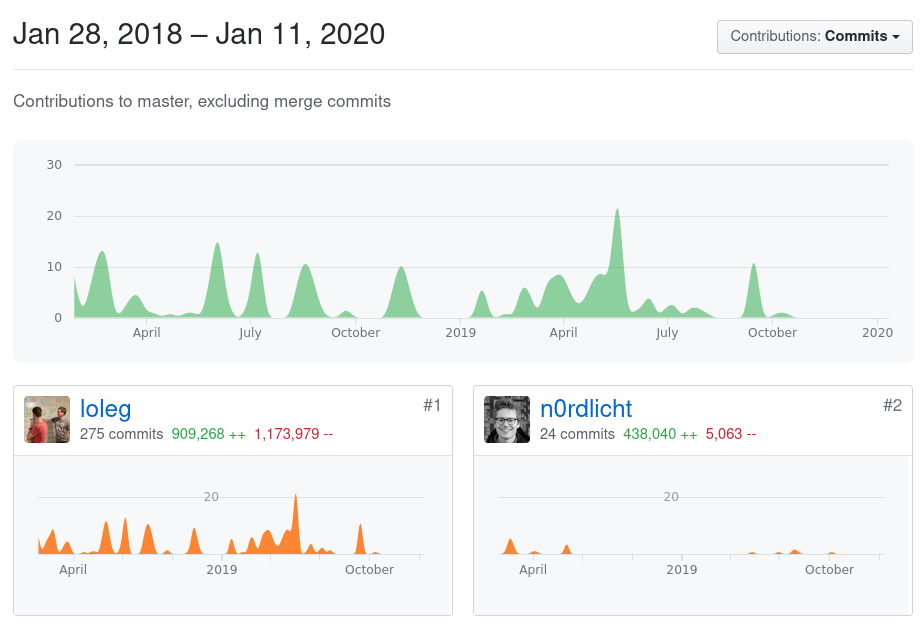

My first commit was on February 1, 2018. Within a week, we had a basic working prototype. An analysis of the city landscape, a map, a Data Package. By the beginning of the next year, we proved the idea, won a spectacular grant, and had an ambitious plan. Two intense years of thinking, exploration, code, now: the crucial question of what it takes to maintain velocity. To those on the outside, it may not matter, but when you are part of a build team and especially as a founder, you feel the minutes, hours, days and weeks slipping by with anguish and anticipation. Even if the pressure may not be quite as intense as that task of "Nad and Skid"...

With a 12 million dollar budget, Nat and Skid had to lay out an entire city that included a transit system and entertainment attractions for up to thirty million visitors. In his autobiography, Owings remembers the speed with which he had to “become an expert in many fields” and the tremendous responsibility that was suddenly thrown upon him and his partner. He goes on about how he “made up in enthusiasm for what I lacked in skill.” The pair soon developed an agile team of their own and undertook their inherited duties with poise and persistence.

^ The Origin Story of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill by Sean Joyner

Immersing myself into the world of people who dare to imagine the city different, to defy those who disagree, to pursue their thoughts and dreams in a marketplace of ideas, has taught me an improved perspective on the dimensions of space and time in our society. The experiences have helped me to see the streets in a new light, and - crucially - to understand a little more about what it is like to live in a world not of our making, yet to the pursuit of whose betterment we are entitled, free, and in many ways obliged to act upon. That if our actions will be meaningful, it is if they are understandable, uplifting and reassuring to the people who call these places their home. And the realisation that everything we do in the physical realm translates to the digital: that there is a red thread connecting the creative hackathon to the architectural design contest.

But what of the city, and why the drive for understanding and influencing change?

The Fragile Crescent discoveries evidenced the idea that perhaps "cities thrive and survive because they are inherently dependent on creativity to exist."

– Monica L. Smith

Instead of spending more time ruminating on the slow pace of change around us, processing worrying signals from distant shores - Monica Smith's new book can help us to reflect on the wider scope of things, use the lens of urban archaeology in perceiving our slow but certain adolescence as civilization, to appreciate the onward march of cities as probably humanity's oldest and greatest organizing principle.

#WeekendReading pic.twitter.com/xGHV9ng0vy

— Oleg Lavrovsky (@loleg) January 11, 2020

"Come what come may, time and the hour runs through the roughest day." (Macbeth)